(From the Baltimore Jewish Times - 03/20/14 - Clipper City Media - Reprinted with permission)

In Sickness And In Health

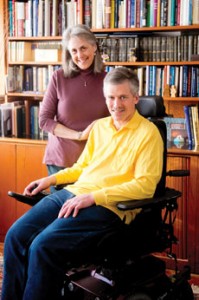

Jan Schein was just 39 when her husband, Dr. Jay Schein, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Although the Northwest Baltimore OB/GYN functioned well for some years after the diagnosis, in 2002, he was forced to retire because he could no longer perform surgery.

“There was a gradual decline,” recalled his wife. “First, we made the decision he couldn’t drive, then he couldn’t grasp knives. This man who used to tie one-handed surgical knots couldn’t tie his shoes.”

The doctor’s life wasn’t the only one that changed dramatically. His wife became his full-time caregiver.

According to the Well Spouse® Association, an organization that provides peer-based emotional support to husbands, wives and partners of people with chronic illnesses and/or long-term disabilities, the United States is home to an estimated seven million spousal caregivers. Known among themselves as “well-spouses,” they live lives they never would have imagined and, in most cases, would not have chosen. But many soldier on, aided by an immense well of inner strength and a handful of support organizations, some of them based in the Jewish community.

After Hershal Cutler’s stroke 12 years ago, his wife, Carol Cohen, felt overwhelmed and unprepared.

At the time of her husband’s stroke 12 years ago, things were on the upswing for Carol Cohen of Columbia. Having become deaf at 22, she had recently completed her doctorate in social work and had received a cochlear implant that enabled her to hear for the first time in decades.

“I was looking forward to my new life,” recalled Cohen.

But before she was able to enjoy her newfound freedoms, her husband, Herschel Cutler, suffered a massive stroke that left him paralyzed and unable to speak. Cutler recovered some faculties later, but immediately following the stroke, Cohen felt entirely unprepared for the challenges that lay ahead of her.

“When your spouse has a stroke, you feel its shock waves. Stroke is often terrifying, and you may feel unprepared to cope with its immediate effects or its long-term consequences,” wrote Sara Palmer, Ph.D., and her husband, Dr. Jeffrey B. Palmer of Johns Hopkins Medicine, in their 2011 book, “When Your Spouse Has a Stroke: Caring for Your Partner, Yourself and Your Relationship.” “But despite your lack of experience or preparation, you are likely to be the first one called upon to respond, make decisions and provide for your spouse’s care. You will probably assume the role of primary caregiver and begin a course of on-the-job training.”

That was the experience of Judi Snyder, whose husband, Howard, had a stroke in 1999, when she was 39 and he was 47. Their three children, two boys and one girl, were 12, 9 and 4.

“Everything happened very quickly,” said Snyder. “I didn’t know what questions to ask. I had never been here before.”

A second stroke shortly after the first took a further toll on Snyder’s husband. Today, 15 years and countless therapy sessions later, he is able to walk with a cane but suffers from aphasia, a brain injury that makes it difficult for sufferers to express themselves verbally and sometimes to understand written or spoken language.

What spouses such as Snyder experience, especially when there are children living at home, is that in addition to advocates and caregivers, they may also become the bread winners in the family or have to relinquish or delay long-term career and educational goals. Most well-spouses experience financial strains due to exorbitant medical expenses and loss of income from a spouse who can no longer handle a job.

Absorbed in all of their responsibilities — merely coping, chief among them — well-spouses can easily feel alone, said Joe Honsberger, senior manager of therapy services at Jewish Community Services. There are resources available in many cases, and people should know that social workers are willing to help.

“It’s always important to talk with someone one-on-one when something like this occurs,” explained Honsberger. “[Talk with a counselor about] what life was like before, what’s it like now, and what does it look like going forward.”

Having someone such as a counselor to talk with is especially valuable once a caregiver is over the initial shock of a spouse’s illness or disability.

Ben Dubin has felt more and more isolated as his wife Esther’s early onset Alzheimer’s disease has progressed.

“The effect on me is that I’m socially isolated,” said Ben Dubin, whose wife, Esther, has early onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Esther’s decline has been rapid; she hasn’t spoken for the past two years, said Dubin. For the past five years, Esther has required in-home care 12 hours a day, seven days a week. She can’t manage any of the activities of daily life, can’t stand up and has lost half her body weight. She is mostly unresponsive.

Dubin is grateful Esther’s sister and niece and a group of his wife’s friends continue to visit her every week.

“They try to make themselves known, by repeating old stories, but it’s getting harder and harder,” said Dubin. Otherwise, “it’s a lonely life.”

Snyder said she and her husband categorize people as “B.S.” (before stroke) and “A.S.” (after stroke).

“Friends from before the stroke are still around, but they’re not in our daily lives,” she said. “I did feel hurt and angry at first, but it’s difficult. They just can’t handle it. I’m not angry anymore.”

Jan Schein described going through the traditional stages of grief, even though her husband is very much alive.

“If I were a widow, I’d have closure,” she explained. “But in this case, there’s an extended grief period with no end in sight. When you get past 10 or 12 [years], it really wears you down. You have to let go of the dreams of what will be and the memories of what was. You have to realize this is a different person. And when it’s your spouse, you’ve lost your partner. Yet, he’s still there.”

These days, Jay Schein uses a walker and has braces on both legs. He has limited use of his left arm and increasing cognitive difficulties including a decline of his executive functioning skills. He is still able to handle his own self-care so he doesn’t qualify for home health care. However, his wife doesn’t leave him alone for more than a few hours because she is afraid he may have an accident.

“I try to come up with activities when he is home because it is important for his health that Jay keeps his brain and legs moving,” said Jan Schein. “Yesterday he went to day care and came home and told me that he made an art project by cutting up leaves. It’s like having your kid come home from day camp. It’s like the whole house revolves around his illness.”

“You have to accept that the person you married is here, but not here,” added one 56-year-old spouse married to a stroke victim who requested anonymity to protect the identity of his family. “My wife has done an amazing job of rehabbing, and to look at her you might not think there’s much wrong with her. But cognitively, she’s like a child. I miss communication the most — all the things a typical couple shares.

“You take one day at a time getting to know and love this new person,” he continued. “We were looking forward to being empty nesters, going on vacations, traveling. That’s gone. It wasn’t in the cards. My kids ask me ‘Why don’t you go on a cruise?’ I don’t know if I want to go on a cruise watching all of the healthy spouses having a good time.”

Spousal caregivers face unique challenges when loved ones suffer life-changing illnesses

Finding Support

Rabbi Richard Address, who leads Congregation M’kor Shalom in Cherry Hill, N.J., has written and spoken extensively on the loneliness of spousal caregivers. He believes that congregations have an important role to play in providing support for well-spouses.

“We hear it all the time from congregants [who are well-spouses]: ‘You have no idea how lonely I’ve become,’” said the rabbi.

Address believes the issue will become more and more prevalent as baby boomers age and medical advances cause people to live significantly longer. Judaism, he argued, needs to adapt to that reality.

“It is time for our community, in light of the revolution in longevity and the blessings of medical technology, to seek a new Jewish legal term that with love and care can better describe this elongated state of life that so many of our loved ones now endure and that so many will come to experience,” Address wrote in “The Uncertain Path: Emerging Issues for the Caregiver,” an article that appeared in the 2012 book, “Broken Fragments: Jewish Experiences of Alzheimer’s Disease.”

While some spouses cherish the extra time spent with a husband or wife who no longer works and has a more relaxed schedule, others find caring for a chronically ill and/or disabled spouse at home is simply not possible. For some well-spouses, placing their husband or wife in a nursing home is a better choice.

As his multiple sclerosis worsened, Dr. Jay Schein’s wife, Jan, became his full-time caregiver.

“Some people choose to leave their marriage, some divorce but still care for their spouse, others are 110 percent hands-on,” said Schein. “It’s not for me to judge. I don’t live in their lives. This was the choice for me.”

When it comes to providing day-to-day help, organizations such as the Jewish Caring Network — a local group that, among other projects, runs the Tikvah House next to Johns Hopkins Hospital — offer free services such as nursing care, medical supplies, hospital visitation, meals, cleaning and laundry assistance, day and weekend respite retreats for caregivers and a range of services for children.

But as for well-spouses’ need for social outlets, “it’s a challenge,” admitted Sara Palmer. “Caregivers have to set limits as to how much time they need for themselves and how much they need for connections with others.”

At JCS, Honsberger urged caregivers to go online to find support groups and other resources. He said that one of the most important things well-spouses can do for themselves is to find others going through the same things they are.

“If they’re feeling angry at the spouse, they need to be with others who understand and can help them to feel it is OK to feel angry sometimes,” he said. “Or they need to know it’s OK to go out with a group of friends. … They need to have a life outside of being a caregiver.”

Schein reaps a tremendous amount of happiness from the well-spouse group she co-leads in Northwest Baltimore. She discovered the Well Spouse Association several years ago at a time when her sadness had become “overwhelming.”

“I had to find socialization and have my own life,” she said. “Being so attached to his illness was strangling both of us.”

In addition to its support groups, the Well Spouse® Association offers phone groups, mentoring, an annual conference, weekend respite events and access to the association’s online forum, website, blog and chatline.

“For the first time, I was reading things [on the website] that were so familiar to me,” said Schein, whose group meets monthly at a café in Pikesville. “I went on my first respite weekend in February 2010. I met these strangers at dinner, and I couldn’t understand why they were smiling and laughing. It hit home then that it was OK to have fun. Just because Jay couldn’t participate didn’t mean I couldn’t.

“I didn’t have to feel guilty,” she continued. “One of the biggest problems we face is survivor’s guilt.”

Other support groups, though, welcome couples. Snyder noted that the people she and her husband met at a stroke support group at Lifebridge Health remain their closest friends.

Judi and Howard Snyder have found that the friends they made at a stroke support group are like “soul mates.”

Meeting them “was more than a relief, it was like finding soul mates,” said Snyder. “Sometimes when you can say [what you’re feeling] out loud to someone and they say, ‘Absolutely, I know what you mean,’ it makes a big difference.”

Dubin belongs to Schein’s well-spouse group as well as a local group affiliated with the Alzheimer’s Association.

“I like that I can say whatever I want and not worry about it getting out of the group,” said Dubin. “Some of what we do is educational, and sometimes I talk about my experiences and maybe someone else can learn from me. Mainly it’s a social outlet, and I don’t have to go to dinner by myself.”

Dubin, whose adult daughter Rachel was born deaf, has long been active in the Jewish disabilities community in Baltimore. Dubin said that clergy at Baltimore Hebrew Congregation have visited during his wife’s illness, and Schein likewise said that having the support of her synagogue community has meant a lot to her.

Snyder, an active member of Beth El Congregation, said she also finds a great deal of support at her synagogue.

“Even to this day, if I go to services or an event, a lot of people ask how Howard is doing,” she said. “It doesn’t seem rote. I think they really care.”

While having young children to care for in addition to a chronically ill spouse can be especially difficult, Schein was quick to note that children can also be a source of happiness for well-spouses.

“The kids are my greatest blessing,” she said. “I raised my kids without ‘happiness ever after.’ They grew up with reality — how you cope and adjust to the curve balls.”

Snyder, as well, was teary-eyed when recalling what her children went through as they adjusted to the “new normal” after her husband’s stroke.

“I’ll never forget David saying he was ‘the man of the house now.’ He was only 12. And Sophie missed her dad reading to her. Ben doesn’t remember much about his father before the stroke. Thank goodness for videos.”

Every year on the anniversary of her husband’s stroke, “we celebrate life,” she added. “I’m not trying to paint a picture like everything is rosy. We’ve had lots of tough days, but I can’t be negative.

“I am so sorry this happened to him,” continued Snyder. “No one would ever want to have a loved one go through this. But I am lucky to have been with this man. He’s brilliant and funny, and I enjoy his company a lot. I can go to bed at night knowing I’ve done all I can and that I will continue to do so because Howard’s worth it.”

For Information and resources:

Jewish Community Services

Jewish Caring Network

Greater Baltimore Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association

Stroke Center at Sinai Hospital

Follow us on